Marcin Kukuczka

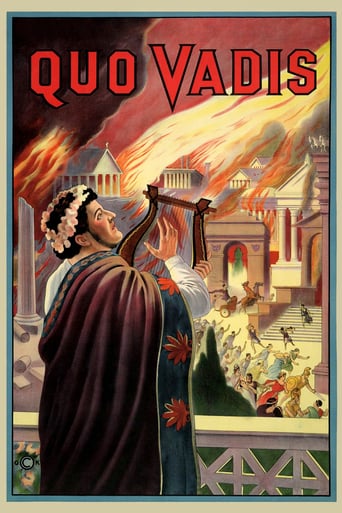

At the dawn of the cinema, it was Italy where actually great spectacles were born. They had the locations at hand. Along the famous CABIRIA made a few years later (which also celebrated its centenary), QUO VADIS by Enrico Guazzoni based faithfully upon Henryk Sienkiewicz's novel, not only stunned the audience of the time being played in many road theaters but also set the standards for the very genre (as many reviewers have stated before me). More to say, Sienkiewicz's novel became one of the top literary sources which inspired so many filmmakers to bring the first century Rome, the decadence and fall of emperor Nero (reigning 54-68 A.D) and the rise of Christianity in the center of the empire to screen. The most famous version enjoying the international renown to this day is, of course, Mervyn LeRoy's (1951). However, great as the ultra popular QUO VADIS is, this one appears to be more faithful to the novel but requires a very special perception. Allegedly, Henryk Sienkiewicz himself saw this motion picture which we can see now after the restoration co-financed by the Lumiere Project.Amleto Novelli, Carlo Cattaneo, Cesare Moltini, Lea Giunchi, Gustavo Serena...the cast of the time do not make any special impression on us these days. Similarly to stagy silent movies of the 1910s, they may appear as 'phantoms' moving within the frame of the screen without desirable close-ups that would instill some understanding of the characters' feelings. Yet, that is not the strength of the movie.The major phenomenon of this silent QUO VADIS (there was another silent version with Emil Jannings as Nero which occurred a flop) are the moments of great aesthetic intensity. Mostly operatic in its feeling, it supplies a viewer with an unbelievable 'image' of the novel's content. It is not the novel so to say 'filmed' or pictured but art of a new medium (at the time) which beautifully combines literature and cinema. With no words necessary, the movie does not disturb imagination but rather inspires its unknown spheres. From the banquet at Nero's through the fire of Rome, the shots of the arena and St Peter meeting Christ on the Appian Way (the climax of the story here though not so historically chronological), the scenes may still occur highly entertaining. We watch a distant past, we have a glimpse of early cinema's vision and both the storytelling and the execution of the content become to us quite 'archaic.' That aspect appears as tremendously involving.There is not much to say about performances, about music score, about special effects. Yet, there is something inspiring about depriving oneself of all the prefabricated expectations of an 'entertaining' movie, about beating the 'cliches' of 'silent film equals to boring film' and allowing oneself to view it in a fresh manner as if it still had something to offer after more than a century. And believe me, it does.

MARIO GAUCI

In the brief introduction preceding the copy I have acquired of this seminal Italian 'kolossal', the hyperbolic epithets of "classic" and "masterpiece" are freely bandied about; while I would not go so far as to use those very words myself in connection with this particular Silent film version of QUO VADIS? (itself the second of 6 film adaptations over the course of a century!), I would gladly agree to call it a milestone – for Italian cinema in general, for the epic genre specifically and, most importantly, for the art of the feature film worldwide. Although MGM's opulent 1951 Technicolor version is easily the most popular of the lot, it is quite remarkable how the actors portraying Roman Consul Marcus Vinicius, Senator Petronius and Emperor Nero here resembled the ones in Mervyn Le Roy's remake – namely Robert Taylor, Leo Genn and Peter Ustinov respectively! Conversely, while Patricia Laffan's sensuous Poppea left an indelible mark in the later Hollywood epic, the frumpy actress playing her in the version under review is anything but memorable. The Greek slave who turns Vinicius' head (and life upside down), then, is portrayed by an actress who, it seemed to me, was way too young for the role but, while her giant servant lacked the magnetism of Buddy Baer, acquitted himself reasonably well in the circumstances. The copy I acquired was clearly a battered-but-watchable one of French origin, accompanied by horrendous computer-generated English intertitles replete with spelling mistakes! As usual with early Silent movies, the overtly theatrical mannerisms affected by the actors gives rise to some unintentionally risible moments; the hot-tempered Vinicius, forever on the verge of slapping his inferiors around, is a particular liability in this regard. Still, like any self-respecting epic to which it paved the way, the overall success of QUO VADIS? is ultimately measured by the spectacle (or lack thereof) on display during the several climaxes integrated into the narrative and, incredibly enough for a movie that is almost a century old, I can safely say that this version of QUO VADIS? does not disappoint: Nero's lavish parties, the burning of Rome, gladiatorial combat in the arena, lions feasting on Christian prisoners (apparently, an unlucky extra became an all-too-real meal for the bloodthirsty felines but, mercifully, the footage does not seem to have been incorporated into the finished film!) and, last but not least, Jesus Christ's apparition to St. Peter on the Appian Way (which meeting, of course, spawned the novel and film's very title).

b-wilkinson-2

Stunning, for its day.I saw this many years ago at the National Film Theatre in London. The acting is stagey, and nineteenth century in style, so it's more excessive than anything that you see in the later Hollywood silent films. But they use real locations, and they tell a real plot - although they are still trying to work out how to do this. Birth of a Nation is a sophisticated modern film in comparison. Things moved very far in a few short years.Oh yes, the lions. Well NFT had got that story in the notes somewhere (that they ate an extra on film), so I kept an eye open. But you couldn't possibly tell one way or another. The scene is a bit shambolic - just as if you'd put a camera in the midst of lions in a circus, and didn't know which the interesting bits were going to be. So, no real closeups. The camera just wanders around, making it distanced, banal, and yet utterly real.If you are interested in film history and get a chance to see this, *do*.

JLarson2006

Probably the first feature film (over 60 min.) ever, this movie has gigantic sets that rival those of movies made years later. All camera shots are stationary, but this doesn't seem to take away from the story much. The story is fairly close to the book with a few liberties--definitely closer than the 1951 version. Obviously the idea of writing a full-length feature film still needed some work. Characters are simply introduced doing things as though the viewer already knows them. St. Peter steals the show in the last half. He's got some great scenes. An important film to watch for anyone who wants to see early breakthroughs in cinema. It's also a good study of early Christianity in cinema.