owckerry

In 1959 an unsolved murder case in Kerry took an unusual twist. The previous November a bachelor farmer named Maurice Moore had been found strangled to death. It says a lot about the distance between community ritual and forensic investigation at the time that, the evening his body was discovered in a ditch, a wake was held in Moore's home in Reamore, at which visitors roamed freely through his house. The following day detectives from Dublin arrived to fingerprint the house. "The whole place could have been found guilty," one local joked.Actually, there was just one suspect. Moore had been due to appear at Tralee Circuit Court a month later after a boundary dispute with his neighbour, Dan Foley. Moore had already told the Garda that Foley had begun to follow him home at night. Photographers camped outside Foley's home in the expectation of seeing him led away in handcuffs. He never was.With insufficient evidence against Foley the case had gone cold the following year when the bishop of Kerry, Dr Denis Moynihan, made an extraordinary plea for information. For leverage he decreed that crimes connected to land disputes were now "reserved sins" in the parishes of Ballymacelliot and Tralee, meaning that only he and his deputy could absolve them. This was a sort of good cop-God cop routine: come forward or risk damnation. It was, as one person described it in Gus Smith and Des Hickey's book, John B: The Real Keane, a frightening development. "It was the kind of extreme action that struck fear into the people of these parishes." And still nothing.Were there any justice in the world John B Keane would never have written The Field, a play about a world without any justice. (A 50th-anniversary production is playing at the Gaiety in Dublin.) The events inspired Keane to write the drama of Bull McCabe, a fearsome tenant farmer whose plans to fix an auction for the field he has long farmed are scuppered by an outside bidder, and whose fatal retaliation holds consequences for his village, his besieged conscience and the frustrated law of God and man.Can the dramatisation of unsolved crimes and miscarriages of justice bring closure? Keane had his own qualms of conscience when writing the play. It was produced, finally, seven years after the events that inspired it, and a few years after Foley himself had died an isolated and shunned man, still protesting his innocence. (His nephew John Foley has continued to defend him and is quoted in a new programme note by Billy Keane, John B's son.) There is an agony in such immortality; to never be found guilty, to never be found innocent, to be eternally on trial.Something strangely similar happened with a new play by Peter Gowen that recently concluded a national tour. The Chronicles of Oggle, a solo performance, is a history of dispossession and abuse in a priest-ridden Ireland whose details are depressingly familiar. So much so, in fact, that Gowen's play reads like a formula.His protagonist, Pakie, moves quickly from his home to the beatings and molestations of a Christian Brothers industrial school and then into an adulthood of resistance and divided communities. But it is also based on a true story, that of a childhood friend who died by suicide in his late 30s after a life scarred by sexual abuse.The "Oggle" of the title is a not-so-veiled reference to Gowen's native Youghal, where the play premiered in 2013. Shortly before it was due to return to the town for the tour, though, its dates were cancelled by the local promoters, who cited complaints from "unnamed sources".That may sound like censorship or a publicity boon – the story became part of the production's marketing material – but either way it lends heft to Pakie's distinction between a singular observer and a timid community: "Two eyes sees all. Ten thousand eyes sees nothing." All of this made it fascinating to read, in these pages, about the musician Cormac Breatnach's intention to make a stage performance based on the wrongful conviction of his brother, Osgur, for the 1976 Sallins train robbery. My colleague Peter Murtagh's article described it as "something of an exorcism" for Breatnach, whose formative years were affected by the miscarriage of justice.Theatre deals with conflict, with trauma and, ideally, with catharsis: you plunge into the depths in order to resurface, with luck, feeling shaken but cleansed. But theatre is ill equipped to bring much of anything to a conclusion. When Donal O'Kelly's play Ailliliú Fionnuala imagined the trial of an oil executive behind the Shell Corrib gas project in Rossport it seemed like wishful thinking for protesters, a reminder that any real-life reckoning was just a pipe dream. The laws of theatre are curious things, endlessly argued.To imagine something may be the first step to bringing it into being, but to witness a fantasy of justice in an unaccountable world seems like simple, perhaps dangerous, placation. It's hard to stage a conflict resolution. An audience in Youghal, for whatever reason, can always look away. After more than half a century a murder suspect is still in the dock. Understand the People, the history, the way of life at the time. this movie shows some of the way we had to life, whether right or wrong . . as an proud Irish person (sometimes we fu** up too) i am not proud of some of our past ' governments,the Catholic church,starvation, but it is our pain, it makes us who we are, Brave movie to make in Ireland .

george franston

The church and the state will steal your property and use it to enslave your neighbours. Praise them and pay them so that they can do this, otherwise you may feel a little bit bad about yourself because some stupid A$$hole told you to.Die so that the machine may build a civilization (an inherently unsustainable and catastrophically destructive series of blocks requiring the importation of resources) where taxation runs around 40% and nobody owns anything due to eminent domain laws. This is so much better than feudalism! I will only pay if you force all of my neighbours to pay as well, that way it's fair!F the world depicted in this movie but f the world we're living in now even more. I'll take 1000000 dead donkies over the life of a good, honest, hard working upstanding man.

info-au-gay

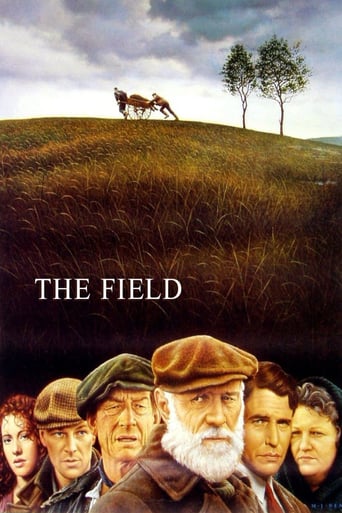

Like JJ, I met John B. (Keane). And, like all good Irish publicans, he greeted all his customers like old friends. After the curtain came down, during Writers' Week in Listowel, there was only one place to be."The Field" is generally regarded as Keane's greatest achievement. He was certainly aware of that fact and had denied it to The Southern Theatre Company (STC), who had opened all, or most, of his other works. But "The Field" was not "Many Young Girls of Twenty" and, for Keane, there was only one "Bull McCabe" - Ray McAnally. Keane was right to wait for McAnally. This was a portrayal of immense power and menace and McAnally literally terrified the audience, such was the intensity of his acting. One left the theater exhausted, yet exhilarated. Bad feeling followed between Keane & Jamas N Healy (Hayley as he was called), the leading actor in the STC. I knew him well & he told me that he could do Bull McCabe as well as any one. Maybe; I never saw him try it.But McAnally's performance - and I went back a second time - has been burned into my consciousness. He finally achieved the fame & honors that were long overdue and his portrayal of Harry Perkins - in "A Very British Coup" - must stand as one of the finest pieces of character-acting on record. But his Bull McCabe was incomparable; definitive - almost impossible to follow.I also met Richard (Dicky) Harris - a fine actor (This Sporting Life - a wonderful portrayal of macho tenderness)- and he was, perhaps fortunate that McAnally's performance had not transferred to film.But good an actor as Harris was, he missed the menace. And I am uncertain about that beard. In my experience, farmers of that period were always beardless; unshaven perhaps, but I felt that Harris looked a bit like Charlton Heston, hamming-up the division of the Red Sea on some back lot in Hollywood, & the performance lost credibility because of that. Maybe Jim Sheridan would disagree?Sorry, JJ; a good effort, but beards are for trade-union agitators; Fidel lookalikes & revivalist preachers.Not hard-working Kerry farmers.

dwarol

I found this movie riveting up until the last 20 minutes or so. After the priest closes the gates to the church, the rest of it degenerates into a poor attempt at Greek tragedy, with Bull having everything stripped from him. There was no need to destroy the man further after losing Tadgh to the Tinker girl and pushing away his wife's one last attempt at reconciliation. Nothing was gained artistically in my view, and that part of the plot made little sense.For example, the body of the American was picked up from a lake just outside Bull's house (the image of the American hanging from the hook and the echo with Shamey's hanging brilliantly suggests all the guilt Bull must be feeling). Along with the donkey's carcass even if it's not proof Bull did the murder, he should have been held for questioning given everything else. Instead, he is allowed to freely walk around and get himself into further trouble.Little things also got in the way for me. For one, the field was just too small, both to support Bull or to support a mill to grind limestone into roadbed. The herd of Bull's cattle he was driving at the end was just too large for the field to feed, and no single man on foot could have driven them a long distance over rocky ground to the edge of a cliff (not to mention previous scenes had shown the path between the field and the sea did not go through the village). Nobody who had ever grown up around cattle such as Tadgh would ever think to get in front of a stampede, even in grief. It would be like someone who grew up in a city jumping in front of a locomotive running at a high speed to stop someone on the train. It just isn't done unless you are suicidal and I don't think Tadgh was at that point. As someone who is actually familiar with that kind of life, director Sheridan's lack of attention to detail suggests someone who really didn't understand farming or who ultimately only really cared about the psychodrama at the story's center. As a result, he only did an adequate job of fleshing out the play into a movie.Still, the acting was excellent throughout as was Sheridan's direction of the actors. The dark layers underneath Bull's life and family were expertly stripped away as the movie progressed. It was a little like seeing the Irish version of "Long Day's Journey into Night". As someone who grew up on a farm, I understand Bull's love/hate relationship with land that he has worked for decades. It really is like raising another member of the family, and no other movie I can think of has ever shown this better than the moving speech Bull gives at one point (I have to wonder if this speech is a carryover from the original play given Sheridan's missteps in showing farming). And the depiction of the grinding poverty of rural Ireland, the entanglement of ancient wrongs on current family lives, and the ambiguous relationship Bull had with the Church all were in accord with my readings of Irish history (and this is an area in which I'm sure Sheridan and playwright Keane are expert).