Robert J. Maxwell

There have been several renditions of the trials (and tribulations) of Oscar Wilde but this is the best. "Oscar Wilde," starring Robert Morley, had appeared two years earlier and was more typical of the way films had to stomp history into a Procrustean bed in order to fit the time slot and please the audience. As Wilde, Morley isn't a pouf but a sensitive soul. He's put on trial and spouts all the apothegms of Wilde's characters as if they were appearing for the first time, improvised on the spot.This version, "The Trials of Oscar Wilde", is longer, more demanding, more historically true, and generally superior. It's informative too. There wasn't "a" trial of Oscar Wilde; there were three trials all in all, one in which he was the plaintiff, one in which the crown prosecuted him and ended in a mistrial, and a third in which he was convicted and sent to Reading gaol ("jail", folks) for two years, during which he lost his wealth, his social status, and his family, and went into exile in Paris.It's not a comedy. At the height of his powers, Wilde has a pretty wife and two children whom he loves. He's also having an affair with the handsome young Lord Alfred Douglas ("Bosie"), son of the Marquis of Queensberry. Whether the affair is Platonic or assumes more physical dimensions, we never find out. Nor in the end does it matter.We don't get to hear the evidence brought against Wilde by four or five scalawags whose integrity is in doubt. Presumably their testimony involved sodomy, delicately expressed. But their stories are tainted enough that we can conclude Wilde was convicted because he LOOKED and ACTED queer. He was tried in the press and was guilty. This was in 1893 in Victoria's notoriously prudent England, but it happens all the time. We're quick to leap on the suggestion of guilt in popular figures. America has just done it now in the case of a once popular entertainer, Bill Cosby. "Schadenfreude" was Freud's word for it, the pleasure taken in seeing others suffer.Most of the characters are given two dimensions except perhaps for the Marquis of Queensberry, the reliable Lionel Jeffries, who is a flat-out, half-deranged sadist. The proximate cause of Wilde's trials, the extraordinarily handsome Bosie, John Fraser, is a moral imbecile, a psychopath, but like other psychopaths he's good at scanning others and generating sympathy for himself. All that's keeping him from being thoroughly "evil" is a German umlaut.Two events are understandably left out. One is Wilde's experience in prison. He did hard time in the sense of back-busting physical labor. Yet he managed to produce one of his better-known poems, "The Ballad of Reading Gaol," from which we get lines like: "Yet each man kills the things he loves" Another absentee is Wilde's death in a modest Paris lodging house, a place he loathed. A visitor found him dying in his bed, staring at the wall. And Wilde said, "Either this wallpaper has to go or I do." He's buried in Père Lachaise Cemetery along with Chopin, Molière, Jim Morrison, and (most aptly) Helois and Abelarde.I found the acting, the writing, and the direction all pretty much above what I'd expected. As Wilde, Peter Finch has to be very careful, as if walking a tightrope. He never acts effeminate except in dire situations, threatened by a knife or pummeled by unwanted visitors. As Bosie, Fraser is a perfectly spoiled and selfish brat. James Mason makes a brief appearance as the court's prosecutor, the guy who was Wilde's classmate at Oxford. ("No doubt he'll treat me with all the bitterness of an old friend.") It's hard to recall a better written summary of the defense than that given by Nigel Patrick as Wilde's barrister and it's difficult to beat Wilde's definition of "the love that dare not speak its name" while on the stand.It's a superior movie.

ianlouisiana

One should always consider the possibility that had Oscar Fingal O'Flaherty Wills Wilde not fallen inconveniently in love with Lord Alfred Douglas he might now be remembered only as a relatively minor Irish playwright with a propensity for presenting other people's bon mots as his own.His ascent to his unassailable position as the Theatre's great gay martyr is at least to some extent the result of his treatment at the hands of the British judicial system. As unpleasing as it may be to sophisticated 21st century thought,the "homosexual act" -as gay love was referred to in Victorian law books - was considered a crime and the "abominable crime of buggery" was punishable by Life Imprisonment.Queen Victoria refused to endorse laws proscribing Lesbianism because she not only had never heard of it but she refused to believe its existence.Aware of all those facts Oscar Wilde chose to sue his lover's father for libel after the Marquess of Queensberry referred to him as a "somdomite" (sic).It says much for his chutzpah if not his intelligence. Mr P.Finch is a fine,sensitive if rather louche Oscar,clearly besotted with the pretty but insubstantial John Fraser.Mr L. Jeffries pushes the boat out a bit as the Marquess of Queensberry,very much an aristocrat of his time with a zealot's hatred of homosexuality as only an old public school man can have.Mr J.Mason is suitably ruthless as his barrister,cold of heart,tongue and eye. This is a handsome film,a typical superior British product of its era, requiring its audience to stay awake and keep off their mobile phones. If you require an instant fix it isn't for you. Wilde may ultimately have been a victim of his own ego,but the Marquess of Quennsberry must be spinning in his grave over his own contribution to his old enemy's immortality.

James Hitchcock

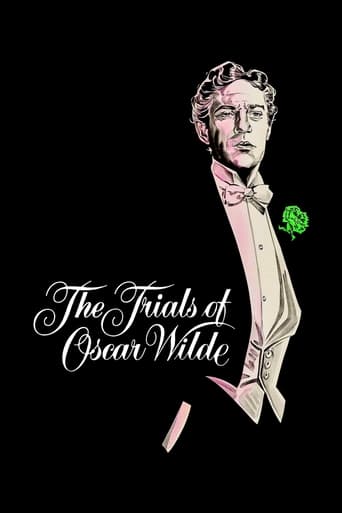

It is sometimes said of London buses that you can wait ages for one and then two come along at once. So it is with films about Oscar Wilde. The world waited sixty years for a film about him, and then two came along in the same year, "The Trials of Oscar Wilde" starring Peter Finch and "Oscar Wilde" starring Robert Morley. There was, of course, a third version in the late nineties, "Wilde" starring Stephen Fry.I have never seen the Morley film, but "The Trials" has a lot in common with "Wilde". Both tell the same story of Wilde's friendship with the handsome but spoilt young aristocrat Lord Alfred Douglas ("Bosie"), and of how Wilde was pressured into bringing an ill-advised libel suit against Bosie's father, the Marquess of Queensberry, who had accused him of sodomy. As a result of the failure of that lawsuit, Wilde was arrested, charged with gross indecency and sentenced to two years imprisonment. Although the two films acknowledge different source material, "Wilde" is clearly indebted to "The Trials"; the two films have a number of scenes in common. In places the dialogue is almost word-for-word the same.There are, however, a number of differences of emphasis. "The Trials", as its name might suggest, places a greater emphasis on the legal aspects of Wilde's case, with a greater number of courtroom scenes. (The word "trials" clearly has two meanings here; it is used both in its legal sense and in the sense of "sufferings"). It omits, however, details of Wilde's life in Paris after his release, and places less emphasis on his relationship with his wife Constance and with his children.There are some notable acting performances in "The Trials", especially from James Mason as Queensberry's lawyer Edward Carson and Lionel Jeffries as the splenetic Marquess himself, a man eaten up with rage and hatred; I preferred Jeffries to Tom Wilkinson who played this role in "Wilde". John Fraser, on the other hand, was not as good as Jude Law as Bosie. Peter Finch was a gifted actor, but I certainly preferred Fry's interpretation of the title role. Whereas Fry made Wilde witty, but also kindly, sensitive and generous, Finch's Wilde came across as too much the dandy, a man who, although capable of impulsive generosity, often used his wit as a mask to hide his true feelings. Only towards the end of the film, when he realises that he is in danger of imprisonment, does he become more emotional.The greatest difference between the two films is that "The Trials" does not actually admit that Wilde was a homosexual. The impression is given that he may well have been the victim of unfounded gossip, of a deliberate conspiracy led by Queensberry to blacken his name and of perjured evidence given by the prosecution witnesses in court. In reality, there can be no doubt that Wilde was gay, and the Stephen Fry version of his life is quite explicit on this point. Queensberry's accusations were largely true, and in denying them Wilde perjured himself. It has become a received idea to say that he was the victim of the ignorant prejudices of the Victorian era and to congratulate ourselves (rather smugly) that we are today altogether more liberal and enlightened. This attitude, however, ignores the fact that for all his talents and his good qualities Wilde had a strongly self-destructive side to his nature. As some of his lovers were below the age of consent, if he were living in the first decade of the twenty-first century rather than the last decade of the nineteenth, he might actually receive, given contemporary anxieties about paedophilia, a longer prison term than two years. Even if he avoided a jail sentence for sex with minors, he would certainly receive one for perjury.It is precisely because "Wilde" is more honest about its subject that it is the better film. Peter Finch's Wilde is the innocent victim of other men's villainy; Stephen Fry's Wilde is a tragic hero, a great man undone by a flaw in his character. Although he is more seriously flawed than Finch's character, however, he is also more human and lovable, and his story seems more tragic."The Trials", however, probably went as far as any film could in dealing with the subject of homosexuality. For many years it had been taboo in the cinema; a film on this subject would have been unthinkable in the Britain of, say, 1930, or even 1950. By the early sixties the moral climate had become slightly more liberal; the influential film "Victim", which some credit with helping to bring about the legalisation of homosexual acts between consenting adults, was to come out in 1961, a year after "The Trials". In 1960, however, homosexuality was still a criminal offence, and there was a limit to how far it could be freely discussed in the cinema. Seen in this light, "The Trials", although in some respects disappointing, can be seen as a brave attempt to tackle a sensitive topic. 7/10

kyle_furr

I had heard of Oscar Wilde before but i didn't know who he was. I had seen the 1945 version of The picture of dorion Gray but i didn't know he wrote it. This movie has Wilde being put on trial for having homosexual relations, there's more to it but I'm too lazy to put it down. Peter Finch does a good job and James Mason is the main reason i wanted this, but i didn't know he was basically only in one long scene as the defense attorney.